The Art of Selling Art: A Contemplative Approach

![]()

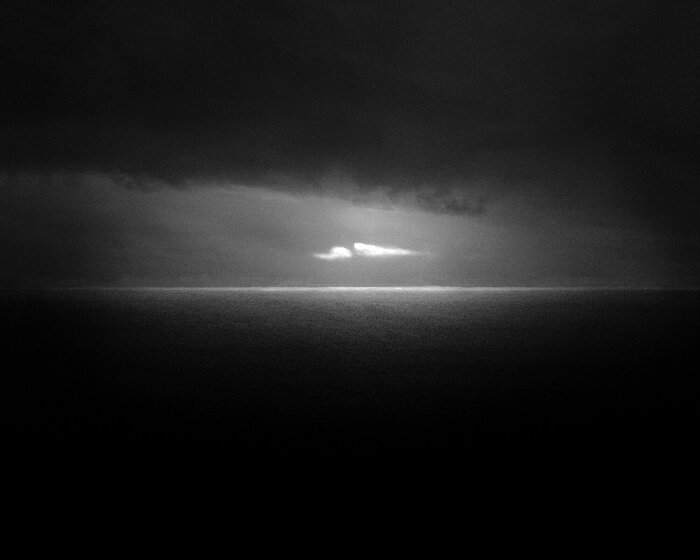

Perhaps the greatest dream of most nature photographers is the idea of crafting a living off print sales alone. All across the internet are stories of individuals making hundreds of dollars off each print, leading to yearly sales of six figures or greater. Unfortunately, this is very often not the case.

What a dream-come-true this would be, to find yourself out exploring nature while people all across the world come to your website and purchase prints of the art you have worked so hard to craft. Instead, landscape photographers — both in the past and the present — find themselves battling against one another for the attention of potential collectors. Though there are millions of art-loving individuals in the world who may wish to purchase a piece of art, there are millions more individuals who are creating art every day, vying for attention. Factor in that a large percentage of these art-lovers are unlikely to be willing to spend the hundreds of dollars many artists ask for their pieces, and you are left with an incredibly small market to gain the attention of. Smaller yet, this market becomes, when you create artwork that is in a specific style, rather than what is trending online.

Read more: The Art of Selling Art: Partnering with Interior Designers to Sell Prints

What then, you may ask, is a potential solution to this issue?

If you were to ask this question to David King Rowe IV, his advice would be along the lines of focusing on the creation of your artwork and the enjoyment of being out in nature. Print sales are likely to come as your work gets better and your name begins to break out into the market more. Spending all your time at home, in front of the computer screen, wracking your mind as you try and figure out how to market your work and gain greater attention – it’s not helpful, nor is it healthy. Speaking to David, he had gone through what most artists do, attempting to make a living off print sales. When he began reflecting on it, however, he found himself at a disconnect with nature. A balance was desperately needed.

Finding a Balance

The idea of using photographic print sales as a sole means of financial stability eventually became a bit of a fever dream for David. Rather than finding it to be enjoyable, it created quite a monumental tear in what he believed in. From the moment he had begun treating photography as an obligatory means of survival – rather than embracing the sacred, harmonious dance between nature and the camera – he found himself to be much less emotionally engaged. Questions revolving around how to market and sell his prints, how many shows a year should be done, which galleries to work alongside of, when to make a book, how large to print, how to sign his name, how many editions, how to frame his work, how often to email past clients to keep up to date, what to charge per print – it all became far too much of a psychological burden to handle.

Recently though, I have found that my mind operates more creatively when there is a balance between the photo world and something separate entirely; a mental barrier that allows a bit of breathing room, giving each photography outing more of a joyous excitement.

Realizing the causation of his stress, David decided to take the situation into his own hands and change his approach to photography, with hopes of bringing back his love for the natural world and the harmonious dance he once performed with the camera. Rather than focus his efforts on print sales and the inundating number of questions it revealed, David chose to work a very stress-free job four days of the week, providing him three full days for flyfishing and photography-related endeavors. This dynamic, he had found, suited his lifestyle and his approach to photography in a much more beautiful manner.

The Intimacy of Small Prints

It seems as though every landscape photographer, for the past few years, has found a fascination with selling large prints. Looking at the print page of any landscape photographer, one will find most purchasable sizes begin around 16×20” – not at all small or what would be considered intimate. But if you look back at artists from the 1900s, this was not at all the case.

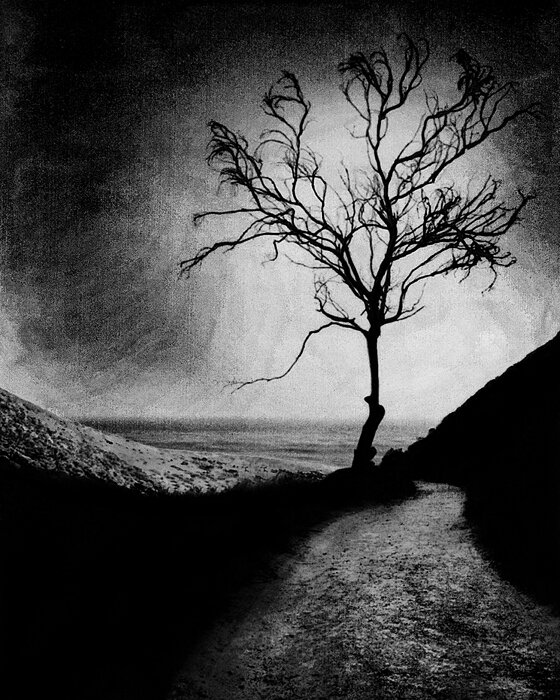

Take Edward Weston, for example. He had strictly done contact prints from his 8×10” negatives, meaning he only sold 8×10 inich prints. There are very few examples of artists such as him anymore, selling such small prints. Perhaps the most famous of them would be Michael Kenna, who had strictly sold 8×8 inch prints matted to 16×20 inchj matboard. Yet even he has found himself allured by the prospect of larger prints, offering 16×20 inch prints to some of his collectors in recent years. It must be said that there is nothing wrong with selling large prints – there are thousands of artists doing it in the modern era and it seems to be what many collectors desire. The intimacy of having a beautiful piece of art that can be held in your hands, mere inches from your face, however… there is quite nothing like it.

That intimacy is what has allured artists like David to follow in the footsteps of Michael Kenna and Edward Weston, offering to his collectors small 8×10 inch and 4×5 inch prints and nothing larger. When viewing a well-executed print of the smaller scale, it reminds David of a beautiful snow globe: “intimate in size, multidimensionally perceived, a glimpse into an expandable universe constructed by the ‘self,’ held in hand by the ‘self,’ made of the ‘self’… DON’T DROP IT!”

He tells how the selling of a print of this size becomes more than just financial gain, as it allows for further understanding between two individuals finding common intrigue in life, in something so intimate. To sell a print to someone who understands what has been portrayed beyond the visual spectrum, to have the connection realized by someone other than the artist themself — it is pure elation.

To further this intimacy, the use of a delicate paper such as a handmade Kozo surely helps. Such a delicate paper — like the photograph itself — must be respected on much more than a psychological manner. A physical respect for the paper while handling it both prior to and after the ink has been sprayed unto it, must be provided. If neglected, if handled in the incorrect manner, this thin paper can be damaged quite easily. More attention to detail is required, with each individual print needing spot healing, as was once done in the days of darkroom printing. Though many may feel as though such requirements would be tedious – “Aren’t we done with that era?” they may ask – David finds it to be very enjoyable and overall calming.

As a whole, it is a very zen-like experience, lacking the robotic immediacy of most inkjet printing today. There is a sense of pride in completing each print, similar to that experience in the darkroom. In addition to the enjoyable process, the actual paper takes on a beautiful sheen, complimenting much of the seascape atmosphere I attempt to portray.

![]()

Selling Prints

In the modern day, there are a number of options each individual artist can take to sell their artwork. The invention of the internet brought on the prospect of selling artwork online, whether through the artist’s individual website or through third-party websites such as Saatchi. Though crafting your own website to show and potentially sell your work is practically required if you want complete control over who gets to see your work, it is not the easiest in the world to gain traction with SEO to gain an audience. Galleries are still a potential avenue as well, though they do not seem to be near as popular as they had once been. Those just getting their name out may find themselves struggling to find gallery representation, as many galleries focus their attention on artists with a large following as it provides them with near-guaranteed sales and attention.

Like with Saatchi and other third-party websites, galleries, too, take a commission on every individual print sale, though the percentages range. Art shows, of course, are yet another manner in which artists are able to sell their work. This way of selling allows the artists to sell their work directly to their potential patrons, meeting those interested in adding the work to their collection, big or small. With this avenue, the main caveat is finding reputable shows where artists can find themselves selling their work for reasonable prices without having to compete with the DIY crafters. Furthermore, like galleries, it seems as though art shows are of a dying breed, especially after the rough year they had in 2020 due to COVID-19.

One way in which few modern artists seem to sell their artwork is through direct conversation with potential patrons. While this may seem similar to art shows – and, in fact, is – the greatest benefit is the lack of cost to such a manner. Such a method as this is not always possible due to how today’s society interacts with one another. Yet there is nothing like selling an intimate piece of art to an actual person, allowing for the benefit of creating a personal, sincere relationship. While many of David’s sales come from inquiries through his website – as well as gallery shows he had had in the past – a nice majority come from relationships he had developed over the years with individual people. Some of these patrons are dear friends to David now, though many he only speaks with a few times per year, if that.

How does he find these individuals? They are not necessarily people who have shown interest in the photography or art world in general but rather have shown respect as human beings in the simplest of ways. The interest in the art world, David has found, comes after having spoken to them for a while, off and on.

People you have worked with years ago; friends of friends; friends of family members; the guy you spoke with at an airport and shared a meaningful interaction with; high school friends; the guy you got drunk with at a college party and for some reason kept in touch and now randomly call each other every few months to share a laugh and catch up with for a few minutes… the list goes on.

The honest interactions had in life — many of which at the time are thought of as not being much of anything other than in the moment — have yielded the most sales and most meaningful transactions in the eyes of David. Though these relationships may take years to come to fruition, showcasing your true self in an honest manner — and ensuring your artwork reflects this honesty as well – David believes it will be surprising who pops out of the woodwork and requests a print.

Finding Motivation

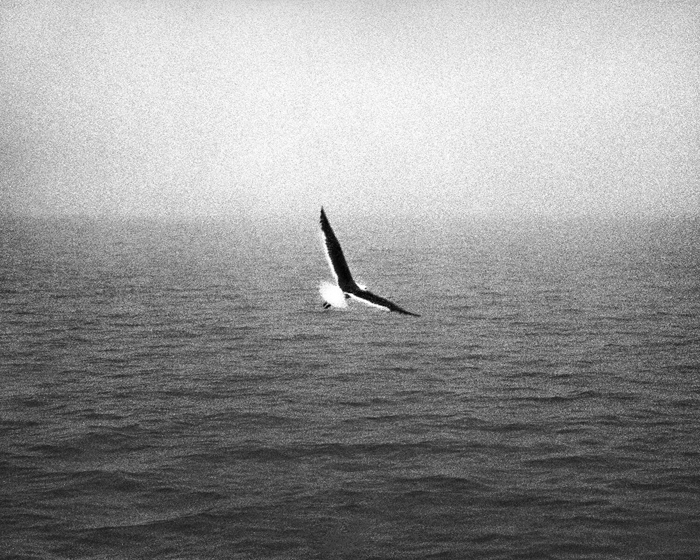

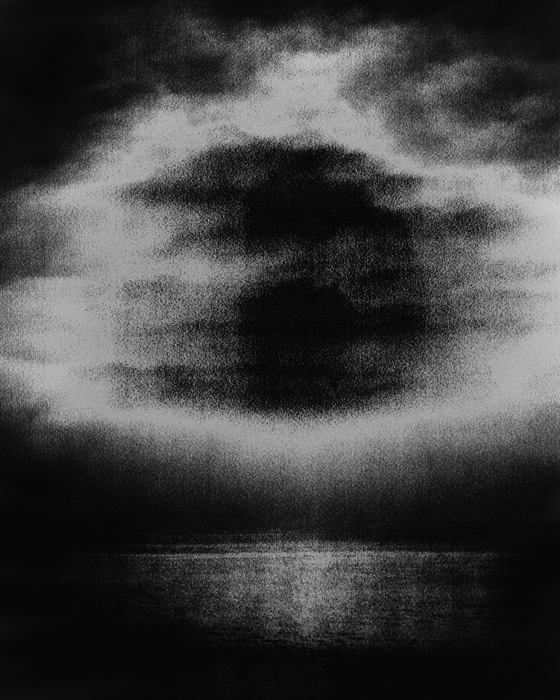

Most of the inspiration for David’s work comes from classical painters and their nocturne studies, along with a handful of early 20th century and contemporary photographers. On a deeper level, however, he finds motivation through exploring the natural world around him. Witnessing new areas of both land and sea are what helps him to continue creating beautiful, intimate pieces of artwork. This exploration helps him to dig deeper into the “self” and reflect upon the past, revealing emotions which can be imbued within his artwork. This reflection, for David, has been crucial to his growth as an individual as well as an artist.

David firmly believes that exploring memories and how they affect the present state can “present your mind with a beautiful dreamstate, almost a flawed logic in form, but real nonetheless.” The importance of shooting while you can, producing the work while you are able, reflecting in the future to come, and finalizing the pieces through whatever process used when you feel inspired to do so, is thusly revealed through this exploration of memories.

Read more: The Art of Selling Art: An Architectural Approach

Future Goals

Like many artists, David, too, used to worry about what people would think of him and his artwork long after he had ended up wherever we humans will end up. Yet this is a dangerous game to play. We think more about how to make our artwork archival, so as to last through generation after generation. But what is the point of this? There is of course a sense of joy in the thought of having your work passed down from the initial collector to their children, to the grandchildren, and onwards. The unfortunate reality, however, is that it is unlikely the successive generations will find within the artwork whatever the initial collector had seen. Instead of the piece being appreciated and hung for all visitors to see, it will likely end up down in the basement or stuck in storage, never to be witnessed again. Why would any artist want such an unfortunate fate for their work? It is better then, it seems, to not worry about the archivability of the artwork. Even after it has long faded and turned to dust, the memories will be alive.

Ingrained in us as humans is what I would call the “legacy construct.” A need to make a name of and for ourselves, to find meaning that transcends life as we know it, from now till the end of time, long after we are dead and gone.

The future for David does not rely on achieving supreme archival standards with his work, nor does it mean that he wishes to create a legacy for himself that will last as long as the legacy of artists such as Ansel Adams or Edward Weston. Such things matter little to David, so long as the artwork he creates connects with his patrons on a personal level.

Instead, David has hopes for the creation of a few hardbound photography books dedicated to seascape and landscape collections. This is something he is slowly working toward by actively taking in new scenery, rather than attempting to rush it, sacrificing the quality, both technically and emotionally. Past this simple, long term goal, he wishes to continue finding pleasure and harmony between the natural world and himself, while learning more about each along the way. There will always be a drive to sell prints to those who truly care and appreciate them, he says, but an active obligation or aggressive agenda will never be done.

Final Words

David’s mental approach to photography is like few modern artists. Rather than focusing on making a living off photographic print sales alone, he had chosen to take a step back and reevaluate his situation. His way of creating his artwork, his manner in which he explored – there was no feasible way to sustain it when trying to answer the hundreds of questions which came up. So he found himself taking a step back, finding a stress-free job to work while allowing himself the necessary time to go out exploring in the manner best for him and his work. This approach may not lead to near as many print sales, but the sales and photography in general will be much more meaningful, much more satisfying. In the eyes of David, creating meaningful work and experiencing beautiful moments in nature is better than selling a large number of prints.

If there is anything I sincerely wish to pass on through this bit of writing, it is the following: stay true to yourself and your craft. Pursue what you love with an open mind and if you truly love what you do, you will find the means to keep the flame alive.

To see more of David’s contemplative, quiet work, be sure to check out his website, and give him a follow over on Instagram.

P.S. If it is within your means, please consider supporting my work through Patreon. Making a sustainable living as an artist can be a difficult venture, even during the best of economic times. Patreon allows individuals to support their favorite artists and creators directly, for as little as $2 per month to as much as your generosity and budget will allow. This support can last for a single month or can go on for as long as is desired; it is your choice entirely. Regardless of how much you choose to pledge, your support allows me to continue creating without having to resort to unsightly ads or undesirable sponsorships. Any support you provide is accepted with gratitude.

About the author: Cody Schultz is a fine art photographer based in Pennsylvania. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and interviewees. You can find more of Schultz’s work on his website. This article was also published here.

from PetaPixel https://ift.tt/3bGmAtf

via IFTTT

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario