Forensic Analysis of a 1965 Photo to Learn Where and How It Was Shot

![]()

Here is a little exercise to show how we can do things in this modern world. This is not one of those whacky geo-location stunts, this is just ordinary research, some simple geometry, and some careful guessing.

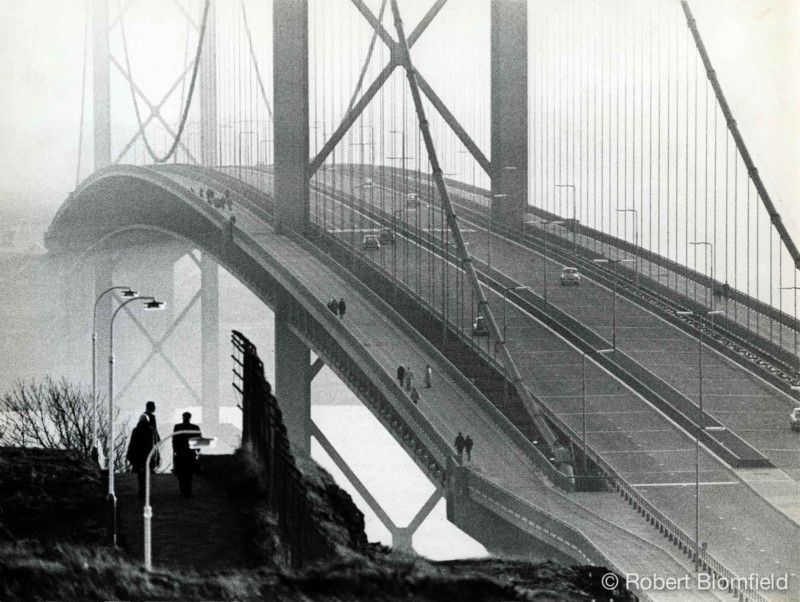

The photo here was shot by Robert Blomfield, of Edinburgh, in 1965. It is the then-recently completed Forth Road Bridge, which crosses the delightfully named Firth of Forth. This picture was recently posted on social media by one account, and then someone else asked if anyone would hazard a guess about what camera setup was used. And so, I did.

These remarks do not reflect my actual thought process, I made a number of false turns and wrong guesses along the way. This is a sort of streamlined version, in which we imagine I made the better guess at every turn, rather than the worse guess. Note that I did all this sitting at my desk in the Northwest corner of the USA. I didn’t have to go to Scotland, not even close. I’ve never been to Scotland. The internet has many interesting things on it, and if you do a bit of careful work, use some available tools, and think a bit you can find out quite a bit.

We will get to the subject of camera and lens in due time. First, let us take a moment to look at the photo:

I am here claiming fair use of this and all the other materials in this post on the grounds of education and criticism.

Let us note a few things. First, the photo is quite soft, and really quite grainy. It gives the impression of something like 3200-speed film, which did not exist in 1965. Second, the perspective is quite extreme. The curve of the suspension cable looks slightly wild. The far tower of the bridge, while visually smaller than the near tower, is not that much smaller, and so on. There is an extreme compression effect in play here.

A quick review: the perspective relationships (how large faraway objects look in relation to nearer objects, and so on) have nothing whatever to do with the camera, lens length, film, etc. They have to do exclusively with where you are standing. The camera/lens combination simply selects a smaller or larger rectangle of what you can see, which focuses your attention this way or that.

Let us, accordingly, work out where the photographer was standing.

The far tower is, according to my notes, 308 pixels wide in the file I have on hand. The near tower is 636 pixels wide, or nearly twice as wide, visually. Let us assume they are the same width, in reality (they are.)

When two same-sized objects are at differing distances, their apparent sizes will be different in the same ratio as the two different distances away. An object half, or one-third the distance away will appear twice or three times the size, and so on. The near tower appears 2.065 times wider than the far tower. If we assumed that we made a measuring error of 5 pixels, we get a range of about 2.05 to 2.08.

Let us examine this bridge on Google Maps. We learn, using the measuring tool, a number of useful facts. The towers are about 3300 feet apart and are about 90 feet wide.

The photographer is some distance in feet, d, from the nearer tower, and is therefore about (d + 3300) feet from the far tower. We know that the ratio of these two distances is probably between 2.05 and 2.08.

Roughly, the far tower looks about half as wide, so the far tower is twice as far away, so the photographer is probably about 3300 feet from the near tower and (thus) 6600 feet from the far one, but we can do a little better.

Hacking around with some simple algebra we find that our photographer is probably between 3050 and 3150 feet from the nearer tower (6350 to 6450 feet from the far tower, about 1.20 to 1.22 miles). Robert was a little closer to the near tower than the near tower was to the far tower, so the near tower is a little bigger than twice as big, visually.

Looking back at the picture, we note that if sight along the frame-left edge of the near tower back to the far tower we hit about half a tower-width to the right of the far tower. We’re looking at a spot in space about 40-50 feet frame-right of the far tower. We can now draw a line on Google Maps with the measuring tool. Well. We could if we knew which end of the bridge our hero was shooting from.

First, note that the cars are going the wrong way, but since this is the UK that means that the picture is not flipped. The bridge runs north-south. We’re either looking north, from the west side of the bridge, or south from the east side. Look at this detail of the car deck and the suspension cable:

![]()

The lowest point of the cable occurs dead center on the span, of course. The “horizon” of the deck strikes me as maybe slightly behind that point, which suggests that we’re looking slightly down on the bridge. We’re certainly not looking up to any substantial degree. A quick web search reveals that the deck of the bridge offers 175 feet of clearance to water traffic, so our photographer is working at least that high. Let’s find a topo map of Scotland: topographic-map.com provides these for us. Take my word for it that we’re looking at the right approximate areas (indicated on the maps with the white sketched areas):

North end of the bridge:

![]()

South end (note that the color coded scale has changed):

![]()

The south end is maybe high enough, but frankly it’s quite flat. The picture at least suggests a hillier area.

Let us assume that the north end is the right end. Vindication awaits. Using the measuring tool in Google Maps (on the satellite view,) we can draw this line, sighting along the edge of the near tower. Starting with an overview:

![]()

Here is the south (far) tower showing how our imaginary sightline lands 50 feet or so west of the tower:

![]()

Same sightline skimming the north (near) tower:

![]()

And finally our hypothesized photographer location. Note the markings for 1.20 and 1.21 miles, to give a sense of the range of possibility:

![]()

Now look toward the highway from our photographer’s location! To the photographer’s right, there are three separate cuts to get down to road level, where just north and south of this location, there are but two. This spot is in fact a high point. This is borne out by the topo maps, albeit approximately, and also by the street view from the highway. Distortion makes this hard to interpret, but you can see two cuts, and then three cuts, in the hillside:

![]()

So we have located a spot where, as far as we can tell, this perspective could be accomplished. What else can we see? What about those guys in the foreground? What’s going on there? There’s a fence, and some streetlights, right? The people standing there look, roughly, 3 times as tall as the people on the bridge at the point where the suspension cables vanish under the deck:

![]()

That is to say, these foreground people are very roughly one-third of the distance away from the photographer than the spot where the cables vanish below the deck of the bridge. After doing more measuring on Google Maps, let’s say they are about 600 feet away from the photographer. Let us look at today’s satellite imagery about there:

![]()

We’re looking at a path around the perimeter of some sort of park. Indicated in red is what might be a fence (the white line on the path’s edge,) the blue circles indicate what appear to be lighting over the path. It is entirely consistent with the same objects we see in the original photo from 60 years ago, although we should suppose the lighting and fence have been updated. A little further south, there are steps on the path, consistent with what looks like the abrupt drop-off beyond the foreground figures. We might even see a little bit of railing, as for stairs, in the photo.

This spot is slightly north and a little west of the North Queensferry Community Center.

I am satisfied that Robert Blomfield went to the high point on the bluff over the highway, and worked his way as close as possible to the highway while maintaining his height in order to maximize the compression from his perspective. The result was impressive, as the actual curve of the deck of the bridge is in reality almost imperceptible. Well done, Robert!

However, we have yet to address the camera and lens. You could shoot this with anything. A modern DSLR with a 28mm lens could produce this, if you cropped the image enough. You’d wind up with a rather small file, but the perspective and framing could be made exactly as this photo is, today. To be fair, there might well be some bushes and things in the way today.

What if you wanted to shoot it straight out of the camera?

A little more research shows that the towers, waterline to top, are 512 feet high. A reasonable guess as to what we’re looking at on the near tower is about (very roughly) 200 feet from bottom of frame to top of frame, at a range of about 3100 feet. Feel free to confirm this, pictures of the bridge are widely available. The 200 vertical, and 3100 range yields a ratio of 15.5 to 1, or roughly 15:1. This same ratio will be reflected in the camera between lens and film plane, because that’s optics for you.

Since we’re not doing macro work here, we can guess that the focal length of the lens is a pretty good estimate of how “far” from the film plane the “lens” is (insert appropriate details about optical centers, infinity focus, and so on.) The lens has a focal length roughly 15 times the vertical height of the image on the film.

So, you could shoot this with a 15mm lens on an 8×10 camera (or any camera with a film or sensor at least 1mm high,) but you’d have to crop to a 1mm height on the film, which might be a bit much. Your picture will be … rather soft.

A better guess would be a 300mm lens on a 35mm camera, which has a film height of 24mm (for a ratio of 12.5:1 which is definitely close enough).

Let us, however, look again at the picture. It’s quite grainy. Like, really really grainy. This could be a fairly extreme crop.

In 1965 the best guess would be a 35mm camera, with various roll-film cameras running a close second. Of course, it could be anything, but these are the likely ones. We could be looking at a 300mm on a 35mm camera, cropped a bit, with some sort of very grainy development. I feel like the contrast might be higher, though. So, eh.

Let us do a little more research on Mr. Blomfield. He’s one of these anonymous, mysterious, fellows who died leaving a shoebox of brilliant photographs, so of course we know more about him than we do about most well-known photographers. He acquired a Nikon F in 1960, a gift from his father, and built up a small collection of primes, including Nikon’s 105mm lens. He favored Tri-X film, naturally. There is no indication that he acquired a 300mm, or one of the extreme zooms that Nikon made at the same time, and indeed one gets the sense that these would have been outside his budget.

Could he have shot this with the 105? He would have been stuck with cropping the frame quite radically, to about 7 or 8mm high, and 9 or 10mm wide on the film, about 10% of the total film area. Given the softness and the grain present in the photograph, I consider this quite likely, and in fact the most likely possibility.

You could take a 1960s vintage Nikon 105mm lens, attach it to a Nikon D8xx camera, and shoot this same photo. You’d crop your full-frame file down to 4-5 megapixels to achieve it. Or, you could use a 70-200 or a 300 on any full frame camera and crop less vigorously. You might need to bring a friend or a machete to manage the underbrush, and you might need to climb over a couple of fences, I’m not sure. I live in Bellingham, not in Edinburgh.

I have to give Mr. Blomfield an immense about of respect here. This was terribly bold, to shoot an absurdly wide view, with the aim of cropping it down to this. His shooting position, rendering this extreme perspective on the bridge, suggests that this was in fact his intention. He went to no small effort to render the bridge this specific way, he must have intended to emphasize this specific perspective. Had he printed the whole frame or anything like it, he’d have a picture of a little bridge over a big body of water.

It’s a bold crop and a remarkably successful photograph. He was aided by the fact that the 105 is a really very good lens, and his technique was, I suspect, excellent. He had been photographing the bridge throughout its construction, for several years, so it is not surprising that he’d found the spot, and this perspective. It’s possible he’d made experiments, and learned that, with the right mood in mind, he could in fact get away with this picture.

Comparing analog to digital in terms of megapixels is a fool’s game, but anyways this photo is probably something like an effectively 1, maybe 2, megapixel photo. Nevertheless, it works.

Fortune favors the bold.

About the author: Andrew Molitor writes software by day and takes pictures by night. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Molitor is based in Norfolk, Virginia, and does his best to obsess over gear, specs, or sharpness. You can find more of his writing on his blog. This article was also published here.

from PetaPixel https://ift.tt/3oYWOpk

via IFTTT

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario